Recently, I mentioned my “Stepping Stone” theory to my therapist. I wasn’t seeking her approval, nor was I hoping she’d dismiss the notion. I was simply, and quite matter-of-factly, explaining an understanding of Life I had achieved at a very early age, and how it applies to me, even now. It started very much as a side note.

I was very relentlessly bullied as a child, my face having a particularly punchable quality to it. It’s the only way I can explain the seemingly uncontrollable desire multiple kids had, growing up, to smash it with a fist, a wall, the floor, or perhaps even a sturdy textbook. My county had a zero tolerance policy on fighting, meaning both students involved were penalized equally, whether or not one of them ever threw a punch. In other words, if I was jumped leaving a classroom–which did happen–and knocked to the floor without having ever touched the other student, I was suspended for fighting. As a result, I spent quite a bit of time in in-school suspension, which seems grossly unfair, except for one detail: I loved it. I thrived in that environment, quickly completing my assigned work for the day, with plenty of time for leisurely reading and quiet reflection. Given the choice, I would have spent my entire school career in the back room designated for “ISS” students.

“Your daughter is going to end up in jail,” my middle school assistant principal once told my mom. “She enjoys getting into trouble too much.”

My mom scoffed at the notion, still embittered by the policy that always seemed to punish me for being beaten to a pulp, rather than protect me from future occurrences. “My daughter likes to be left alone,” she stated firmly. “When she’s in [in-school suspension], she can get her work done, without other kids picking on her and bothering her.”

“Mark my words,” the man insisted, narrowing his eyes threateningly at my mom. “Your daughter is nothing but trouble.”

While marking me as a future lawbreaker because I spent so much time bleeding on the floor of the school halls is hardly the mark of a good school administrator, my mom was absolutely correct: I thrived in that environment, because it was the only place in school I felt safe. I didn’t have to worry about being bullied or injured. I was able to utilize the atmosphere to study and learn, without the constant fear of violence. And even though that should be the premise of every school, it was not, even back in the 1980s and 90s.

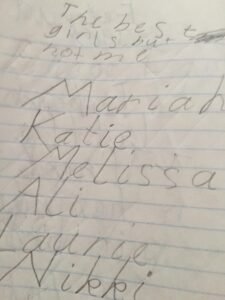

My mom kept my self-deprecating list of classmates

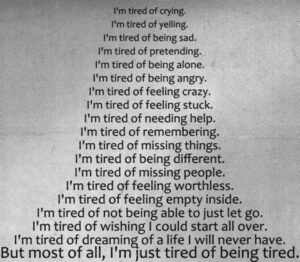

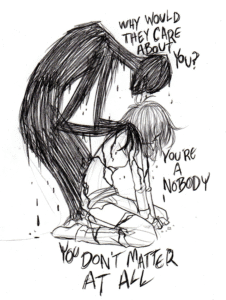

I was always quiet, the weird loner, in multiple senses of the word. “Different” was unacceptable, and my interest in books over fashion, the strange vocabulary I used, my tendency to sit close to the teacher’s desk for increased protection from bullying, and a slew of other factors contributed to the bold red target on my head. I was a thinker, rather than a talker, constantly seeking meaning and purpose in everything in the world.

I was 7 or 8 years of age, before I was satisfied I had figured out my life’s purpose. Time and time again, I had seen the very people who dedicated their days to making me miserable collect praise and awards. While my grades suffered, largely due to my inability to focus and my deeply rooted hatred of school, they were consistently making the honor roll and accumulating various accolades. I took notice how my bullies all had one thing in common: they were all successful, academically and socially.

At the time, I was hearing the same cliches people parrot now: “Bullies torment other kids, because they feel badly about themselves. They’re insecure.” I never fully believed that to be true, chalking it up to a poorly made conclusion by someone trying to justify their own suffering. It all feels very ironic, that we feel we have to boost ourselves, victims of bullying, by making ourselves appear stronger and more put together than our offenders. Aren’t these divisive classes of superiority what really initiate bullying? It certainly doesn’t contribute to ending it. I could run this loop in my head all day, but it all comes down to little more than victims projecting onto the offender: “surely they treat me this way, not because I’m flawed, but because they are.” I suppose, if you want to take back control, it’s natural to make it look like the other party is the weak one.

I had my own theory.

Even at that young age, I was able to acknowledge life doesn’t exist on a level playing field. If someone is going to be successful, they need to separate themselves from the mundane. “No one can do great things in life without confidence,” I told myself. “And if someone is going to gain that confidence by putting me down, then so be it.” I knew I wasn’t destined for greatness, so I was content in my role of Sacrificial Lamb, an example of “mundane” other kids with promise could compare themselves to, in order to achieve that boost of encouragement to go on and achieve amazing things in life.

My therapist stopped me immediately. “You claim others say bullies are insecure, because the victim is looking for a way of justifying their suffering. Are you not doing the same, by assigning yourself a purpose in abusive behavior?”

While I saw where she was coming from, I disagreed, flashing back to “The Incredibles.” In one scene, Mr. Incredible rants, “They keep creating new ways to celebrate mediocrity, but if someone is genuinely exceptional, they shut him down because they don’t want everyone else to feel bad!”

Later, young Dash is upset at being forbidden to use his gifts. “Our powers make us special,” he insists.

“Everyone is special, Dash,” his mom replies.

Dash sulks, mumbling, “Which is another way of saying no one is.”

And later in the movie, it’s villain Syndrome who brings this notion directly to the forefront, declaring, “When everyone is super, no one will be.”

These are all critical life lessons we should be embracing, rather than denying for the sake of feelings and political correctness. Decades before Disney Pixar tried to make this point, I had already reached the same conclusion. I was the weird kid, the reject. But in being such, I had my own unique purpose to serve, which was to allow others who actually had potential in life to look at me and realize what they didn’t want to be. I was a stepping stone, someone they used as a means of realizing they were better than others, a mentality they would then use to be successful in life and achieve wonderful things.

“Not all of us hold the same level of promise,” I told my therapist. “Society wants to pretend we’re all equal, we all have the same amount of promise and opportunities, we all have the same value. Because it’s not politically correct to admit one child has less value than another, even though it’s true. At least I’m realistic enough to have figured this out early in my life, so I could find peace with it.”

My therapist paused to mull the words over in her head. I knew she would never come out and say I held a valid point; no therapist is ever going to admit some kids have to be the sacrifice, so others can reach their potential, even if it does hold truth.

“I guess it depends on what you think gives value to a life,” she finally uttered.

For me, the answer is far more complex than I’m willing to segue into right now, but I feel it’s derived from a combination of potential and fulfillment to others.

My life never had that potential. I was never going to be anyone great, and I was never to accomplish amazing things . My life’s purpose was to fulfill a need for others, a need for the confidence necessary for them to realize they were special and should pursue greatness.

I don’t feel, even now, it’s an absurd notion that some of us exist on this planet in a support role. Am I trying to find purpose in years of being bullied in school? Very much so. However, that doesn’t mean I’m wrong. You may not like this purpose, because society teaches us to frown down on the notion that some people are meant to serve as examples to others of “what not to be.” But disliking or finding it an unfavorable notion doesn’t mean it’s not accurate.

The doctor who will someday cure cancer has to believe they are smart enough to try. Something has to have given them the confidence, make them realize they are exceptional enough to take on such a project. Why is it so hard to believe kids like me exist(ed), to help them nurture that confidence? Not all of us are destined for success. Some of us do, in fact, exist in that support role, a sacrifice so others’ potential isn’t wasted.

Anyone who disagrees, I truly think, is fooling themselves into a politically correct mentality where we’re on equal footing. And I think believing that is far more tragic than finding purpose in rejection.

Categories: Uncategorized

Leave a Reply