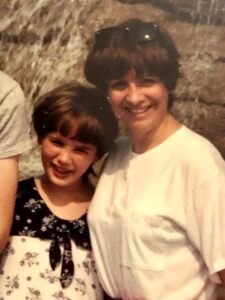

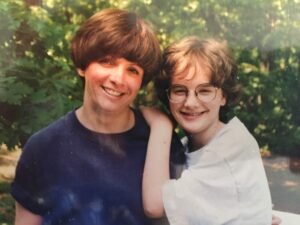

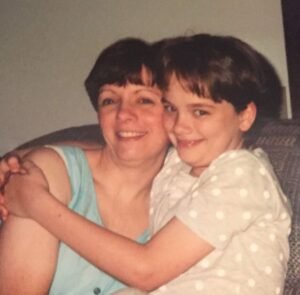

I can think of no better way to describe the events of October 11, 2014 than “the silent goodbye”. How does one say goodbye to someone they’ve spent their entire life loving so deeply? How do you acknowledge they’re walking out of your life forever and into the permanence of Death? Of course, if you haven’t heard this story already, you’re also probably wondering why I’d make a statement as ridiculous as “I killed my mother”, when everyone knows she died from a very rare and hugely aggressive form of cancer. Bear with me, as this is a very emotional tale for me to tell, and I’ve never been able to put it into writing, without freely sobbing.

For most of 2014, my mom suffered, and by summer, we both knew what everyone else refused to acknowledge: her time was very limited. She was nearly five years past the expiration date doctors had stamped on her life upon diagnosis, and it all seemed to start catching up to her at once. When she tried to talk about it to her sisters and my father–she needed to talk about it–they all dismissed her with a wave of their hands. “Don’t speak like that,” they told her. “You’re going to be fine.” So it fell on me, her 33 year old daughter who was still struggling to cope with her newly diagnosed mental illnesses, to have those difficult conversations.

My Disability status meant I spent every single moment with her, a true blessing I get to look back on with fondness instead of regret. I was her primary caregiver, and I took the role seriously and with great pride. I’d make sure she took her chemo pills, fought with her to eat or drink, clean and sterilize the floors when she’d miss her puke bucket, sometimes bathe her and brush her teeth–it’s ironic that I wasn’t able to work a full time job I’d get paid for, but I very much held one at home.

Mom had always been a high energy multi-tasker, and I often joked she was more manic than my episodes were. But that summer, her body no longer cooperated, and she spent most days curled up on the couch, staring out the window. It was a complete contrast to the Mom I knew my entire life, and I’d always be on the opposite side of the room, sitting sideways on my recliner, so I could face her. But one afternoon, I had been staring at her and had a deep, undeniable feeling I could read her mind. I relocated to the floor in front of her and rested my head on the sofa cushion next to hers.

“Open or closed,” I said quietly, with no further context.

I got my confirmation on my mind-reading abilities, when she quietly whispered, “Closed.”

“Pink or yellow?” I asked, as my follow-up question.

Mom opened one eye in a squint, and in a barely audible voice, replied, “Surprise me.”

I chuckled at her sense of humor, still present at such a time. But that’s how she and I planned her funeral, while the most important people in her life refused to acknowledge the reality of her situation. (For the record, her indecisiveness led me to ensure my aunt bought both pink and yellow roses, a tribute to that moment we shared, that no one else understood.)

By fall, she was constantly in and out of the hospital and declared upon arrival home, “When I go back in the next time, I’m not coming out alive.” And while the statement was again dismissed by my father and two aunts, I completely understood this to be fact. She had become extremely weak and looked very much like a Ping-Pong ball, when trying to walk down the hall. I used to follow behind her, my arms held out on both sides of her, as she’d constantly lose her balance and bounce from one wall to the other.

Getting her to eat or drink was my greatest challenge, and I often had to get firm with her, in some sort of strange role reversal where child becomes parent. “What do you want to eat?” I asked. “Whatever you want, I’ll go get it. Do you want some gumbo? I’ll go to New Orleans. Do you want an In-&-Out Burger? I’ll take the next flight to California. Whatever you want, I will make it happen. But I need you to eat.”

“Salisbury steak,” came her reply, and I was immediately taken aback and confused. The look on my face told her I needed further explanation, so she reiterated, “Salisbury steak. One of those TV dinners, with mashed potatoes and corn.”

“Are you kidding?” I laughed. “I just offered to go to the ends of the earth for anything you want, and you want a damn frozen TV dinner from Walmart?”

“Salisbury steak,” she repeated. “With mashed potatoes and corn.”

I shrugged, grabbed my keys, and walked out the door. “Don’t get up until I get back,” I ordered, a familiar demand when I had to leave the house and was worried about her falling. “I’ll be back in 30 minutes.”

True to her word, she did attempt to eat her TV dinner, finishing roughly half of it, and I watched with a mixture of amusement of her choice and gratitude she was finally trying to get something into her stomach. I kept an eye on her the entire time, and nothing seemed amiss. This is a moment I regretted for a time, but I’m again getting ahead of myself. Again, this is not a story that’s easy for me to tell, so my brain is often scattered when I try to do so.

About a week later, she took a turn for the worse and started declining far more rapidly. The tumor near her temple was growing very literally by the day, the tissue turning black and necrotic. It was a truly grotesque and horrid sight taking place right before our eyes. Doctors originally declared another radical surgery would be necessary: they’d remove the flap in its entirety and take more of her face, a large portion of her scalp, and her right eye, before grafting a new flap to it. “When the cancer gets into your eye,” they warned, “it will be the most excruciating pain you’ll ever experience.” But before she could make the decision to move forward, hesitating for only a moment as she described her future as “looking like a patchwork quilt”, the same doctors took the option off the table. “It’s growing too fast,” they explained. “It’s like a spiderweb taking over your entire head, and that webbing is spreading in all directions, far too fast for us to stop. Surgery is no longer possible.”

Still, everyone but Mom and me remained steadfast in their denial. She had proven the doctors wrong this long, so certainly she’d continue to do so, they surmised. But Mom and I knew she was on borrowed time.

Then, on October 11, 2014, everything came to a head. I was at the end of my rope, exhausted both mentally and physically, and fighting my own losing battle to get her to eat or drink anymore. She wouldn’t take her medicine, wouldn’t put any food or liquid to her lips, and was projectile vomiting. Her blood pressure was fine, and she had no fever, but I called my father anyway. “You have to take her to Emory,” I wailed. “I don’t know what to do! She’s vomiting everywhere, she’s got nothing in her stomach, she’s lethargic, and I just don’t know what to do!”

When he told me he was on his way, I began the familiar routine. “He’s coming,” I warned my mom, and she groaned weakly in defiance. “I’m sorry, Mom. But I just don’t know how to help you. You need to get IV fluids or something. If you won’t eat or drink, I can’t take care of you.” But as I spoke those words, I remembered what she said about not returning home after her next hospital stay.

I guided her to the bathroom, where I packed her bag and helped her put on a pair of pants and shoes. I was tying her laces, when I heard the door of my father’s truck slam shut. He was not a man who liked to wait, and it was always up to me to make sure Mom was ready and waiting by the time he got home to get her. And since she was again taking her sweet time, I retreated back to the living room and sat in my recliner, leaving the two of them to argue by themselves. Shortly after, he stormed back out the door, walking past me without a word, and waited in his truck.

Mom slowly shuffled to the front door, then paused and turned to face me. The look on her face said more than 10,000 words ever could, and I suddenly understood for certain what was happening. She was about to walk out of my life forever, and there was absolutely nothing I could do about it. We remained staring at each other, neither of us speaking, and years later, I wonder if her mind raced as much as mine did in that moment. I wanted to go to her, to hug her, to wrap my arms around her and sob, but I knew I would never be able to let her go. I believe she felt the same way, because instead of continuing our lifetime of tight hugs and comforting cuddles, she simply offered me a weak smile that projected so much of her own sadness.

I shut my eyes tightly for a moment, nodding in silent understanding. When I opened them again, we continued to stare at each other across the room for several more long seconds, before she opened the door, then turned around and offered a small wave. I remained paralyzed, willing myself to not cry. No, I would not cry. It would only make things so much harder, if I broke down in front of her. Instead, I took a deep breath, and as a sign of the internal devastation I was struggling to hold at bay, the first tear slowly leaked down my cheek. I wiped it away and again nodded in understanding.

And with that, she turned around, stepped out the door, and closed it behind her.

My mom had just walked out of my life. She was gone forever. The house would always be empty, and something in my life would always be lacking. My amazing mom, my best friend on the planet, the only person in my life who had always been in my corner from Day One, through all the adversity, my self-declared #1 fan who loved me when no one else did, had just walked out of my life, and I knew she was never coming back. And only when I heard the truck pull away from the driveway did I allow myself to freely cry, releasing the metaphorical floodgates. On October 11, 2014, I said goodbye to my mom forever…without ever uttering a single word.

Days later, she slipped into a coma, but I didn’t visit her at first. I had already told myself our “silent goodbye” was the best way, and I declined every invitation my father extended me to visit her at the hospital. I wanted to remember her the way she stood in front of me, not hooked up to life support. And though I can’t tell you why, I awoke one day and decided to change that. I wanted to see her, even though I knew she couldn’t see me or speak. I called my brother and invited him and Jess to come with me, and they were more than happy to accompany me for the ride to Emory Johns Creek.

Perhaps you now understand the first part of my title but are still wondering how I killed her.

That day in ICU, the doctor was going about his usual business of suctioning the lungs of my comatose mom. She had been diagnosed with pneumonia, so this procedure occurred several times a day. But almost as though fate cruelly paired with irony, the one time I was present, a discovery was made.

“This is a corn kernel,” the doctor said with puzzlement, as he admired the contents he pulled from her lungs. “When did she eat corn?”

Everyone in the room looked at one another, confused, as it had been more than a week since she was conscious, let alone had anything to eat. But as everyone shrugged and looked at one another, I was slowly and timidly backing up into the wall behind me, wanting to disappear. Finally, all eyes focused on me.

“I gave it to her,” I confessed, barely able to get the words out, as I was flooded with the realization she had aspirated on the corn I had given her with the Salisbury steak TV dinner. I had watched her eat it, and she never coughed or choked, but somehow, she still managed to aspirate, likely causing the pneumonia. My father was infuriated, though I’m not sure if he was angrier that I so foolishly gave her corn–as though I was supposed to somehow predict the outcome–or that I hadn’t known she had aspirated. But he made it clear: THIS WAS MY FAULT.

If you read my previous blog entry, you know she was removed from life support later that month, and the message was still clear from my father: I KILLED MY MOTHER. I gave her the corn. I was in charge, and I fed her something that she aspirated on. Worse, I didn’t even know she had. If I hadn’t done that, she would still be alive.

And for several years, I believed this to be fact. It was forcibly shoved into my head that I, not terminal cancer, was solely responsible for my mother’s death, and I silently carried that burden with me for the next 4-5 years.

Then one day, I confessed to my aunt during one of my trips to New Orleans, but not from guilt. I had accepted that I likely didn’t kill my mom, but in a strange twist, I rather hoped I had. My aunt was devastated that I had carried such a heavy burden by myself for so long, as well as furious and disgusted with my father, but I explained my new mindset:

“We will never know if that kernel of corn triggered the pneumonia that ultimately killed her,” I said. “But if it did, then I’m glad I gave it to her.”

My aunt stared at me, unsuccessfully trying to hide her horror at what seemed a heartless statement.

“The doctors said if the cancer went into her eye, it would be the most excruciating pain she ever endured,” I continued. “Do you remember?”

My aunt nodded, clearly waiting for this to go somewhere relevant.

“The day I visited her in the hospital, I lifted her eyelid. I was curious. And it was there. I could see it.”

My aunt very audibly gasped, suddenly aware what I was trying to say.

“The white of her eye was already turning a dark red color. It was there. But she didn’t have to feel the pain the doctors warned her about. I don’t know for certain if I expedited her death, but I like to think I did, because it spared her from having to endure that level of suffering. I want to believe it was my final gift to her.”

My aunt dropped the laundry she was folding and hugged me as tightly as she could. “I don’t think you killed her,” she said, her voice quivering, “but you can believe whatever you want to. However it played out, you’re right. She didn’t have to suffer in the way they predicted.”

And that’s how I killed my mother. The only friends who know I’ve always felt this way have tried to convince me otherwise, but I’d rather they not. I’ve found peace in my role. I want to believe I helped spare her from unimaginable pain. It may be a bizarre, macabre statement to some, but I view it with pride. It is 100% certain that she would have suffered immensely more, had she been conscious. The cancer was in her eye, and that wouldn’t have changed, no matter what I did or didn’t do. It was there. So I absolutely like to think I had a hand in sparing her from that. She was ready to go, and she was able to do so without that unfathomable suffering.

I killed my mom. And I’m fine with that. I’m proud of that. I’m happy I was able to give her the peaceful departure she wanted and deserved.

But truth be told: I’d rather not look at another Salisbury steak TV dinner again in my life. I may have killed my mother, but I still can’t look at a frozen Salisbury steak without crying.

Categories: Uncategorized

Leave a Reply